Training Adaptations

⏱️ Reading time: ~5 minutes

The first thing to consider when planning your strength training sessions is which adaptation you are trying to achieve. Do you need to get stronger or faster, do you need to improve stability or mobility, or do you need to build muscle? Without having a clear understanding of what you want to get out of training you cannot effectively plan your session to bring about the desired outcome.

There are many specific adaptations we can achieve through training and they are all determined by a number of different variables including the exercises we use, the order we perform the exercises, the intensity of the training, how many sets and reps we do, how fast we perform each rep, how much rest we take between sets, and how often we train. All of these variables must be taken into consideration and modified to elicit the specific physiological response we need. I will talk about these in depth in future posts.

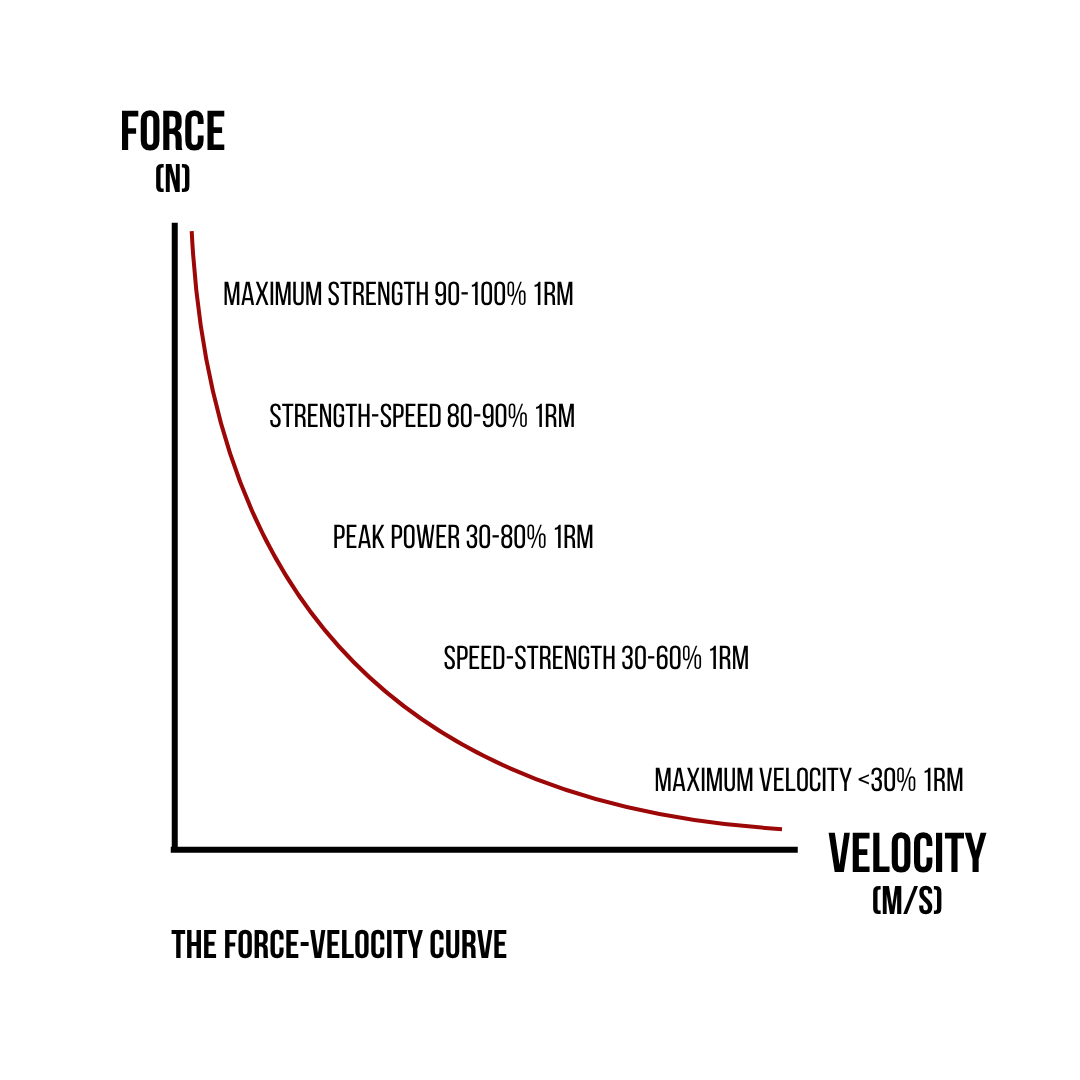

The force velocity curve illustrates the different strength qualities we can gain from strength training each of which require specific training modifications. There is an inverse relationship between force and velocity meaning an increase in force causes a decrease in velocity and a decrease in force allows for an increase in velocity. As we move from maximum force to maximum velocity we can manipulate the training variables to stimulate the specific strength quality needed to improve performance.

Maximum strength

Maximum strength is the maximum amount of force we are able to produce during a specific movement. Using the back squat as an example, this would be the maximum amount of weight we can load onto the bar while being able to squat to a pre determined depth and stand back up again for one repetition. When training to improve maximum strength we need to be lifting in the range of 90-100% of our one repetition maximum (1RM) and typically use compound exercises like squats and deadlifts.

Strength-Speed

In the strength-speed zone we are using near maximal loads at around 80-90% 1RM but with the intent to move the bar faster than we can in the maximum strength zone. So we have slightly lower peak force production but we are able to achieve higher movement velocities. Strength-speed can be developed with exercises like the clean and jerk.

Peak Power

The middle of the force velocity curve is where we are able to produce peak power output. With loads of between 30-80% 1RM we are able to produce the greatest amount of force in the least amount of time. Power would typically be developed using exercises that can be moved fast with relatively heavy loads like olympic lifting variations, loaded jumps, depth jumps etc.

Speed-Strength

In the speed strength zone the goal shifts further towards speed development. Loads of between 30-60% 1RM do not achieve either peak power or peak velocity but do allow us to express faster muscle contractions than with peak power training which can be useful for transferring strength and power into movement specific skills like jumping. Exercises that would be used to develop speed-strength include lighter loaded jumps and any reactive type exercise where the ground contact time is slightly longer than in true plyometric exercises.

Maximum Velocity

Maximum velocity is on the opposite end of the curve to maximum strength and is essentially the fastest speed that we can move through a specific movement and therefore requires little to no external load. With maximum velocity, loads of less than 30% 1RM are used to allow us to generate the fastest muscle contractions possible. When training for maximum velocity we would see the use of plyometric exercises like leaps, hops, drop jumps, sprinting, and even assisted variations to add an ‘overspeed’ stimulus.

Understanding which strength quality to chase and at which time is key for improving your performance. Training for maximum strength comes at the expense of maximum velocity and vice versa so relentlessly chasing one over the other can be extremely detrimental. Another adaptation which we haven’t mentioned but is probably the most obvious is muscle growth.

Muscle Growth

Although muscle growth may seem to have a smaller impact on your performance than strength and speed it is still an extremely important adaptation we must take into consideration. Muscle plays a huge role in the development and expression of strength and also reduces the risk of injury. Within reason more muscle mass is beneficial for performance because it allows you to be more physical. Mass moves mass and if you are undersized you will have a hard time competing against bigger, more physical players. Training for muscle growth typically requires loads anywhere between 30-80% of our one repetition maximum taken close to muscular failure.

The adaptation you choose to or need to develop will depend on your current physical abilities and your goal. If you need to get stronger you’ll need to focus your efforts towards maximum strength. If you need to get faster you’ll need to focus your efforts on maximum velocity. If you need more muscle mass your training must place more emphasis on muscle growth.

It is important to note that these adaptations can and more often than not should be trained concurrently. The emphasis of your training can shift to prioritise any one quality over another strategically throughout the training programme.

Knowing whether you need to get stronger or faster or add more muscle mass is generally fairly intuitive. My advice would be to improve all aspects of your performance and periodically focus on one aspect that you think will benefit your game the most. If you are feeling the strongest you’ve ever been but feel slower and less bouncy it’s clear that more maximum strength training is not the answer.

So what are your current weaknesses? Find out what you need to improve and you have a starting point to build a programme that will take your athleticism up a level.